Real people, Real research: Searching for dugong & surveying seagrass in Sulawesi

Angélique Bonnet

December 13, 2016

Angélique Bonnet

Intern at Alterra, Wageningen Environmental Research, the Netherlands

Agronomy and environmental sciences engineer degree at the ENSAT, France

This research assessed the spatial distribution, species composition and status of seagrass beds in addition with dugong status, distribution and threats in Sulawesi, Indonesia.

How did you get involved in doing a research on dugongs? What was the objective of your research?

This research on dugongs is part of two projects conducted in Indonesia by Yapeka, an Indonesian NGO, in collaboration with Alterra, research center in the Netherlands. Yapeka is developing Community-Based Marine Protected Areas and Alterra has strong knowledge and experience on building and implementing ecotourism plans for sustainable development. This research is the first project in which the Indonesian partners cooperate with Wageningen UR and provides important input for the conservation of biodiversity and sustainable development in Sulawesi, Indonesia.

Robust scientific data were lacking concerning the status of the different ecological structures and especially seagrasses. Also, data on dugongs were not available in the area or were at least very sparse and localized. This research aimed to assess the spatial distribution, species composition and status of seagrass beds in addition with dugong status, distribution and threats.

Indeed, we created baseline seagrass distribution maps using data collected in the field and GIS techniques. In addition, we highlighted the status and distribution of dugong populations within the proposed survey area, identifying threats and proposing mitigation measures. Dugongs could become flagship species to increase conservation efforts in the area.

Why did you chose Sulawesi, Indonesia for your research?

Sulawesi Island, Indonesia is located in the center of the Coral Triangle, area of the world with a very high biodiversity of corals, reef fishes, mangrove vegetation and seagrass.

In addition, sightings of dugongs are known to occur in the area and the Sangihe Islands are currently considered as a corridor of dugong migration path from Indonesia to the Philippines.

Therefore, this area is a critical area for biodiversity conservation currently facing multiple threats. For instance, recently, the coast near Manado is facing an important coastal development which might impact directly marine biodiversity. It is urgent to manage the area for sustainable development and conservation of these remarkable ecosystems.

Whereabouts in Sulawesi did you go?

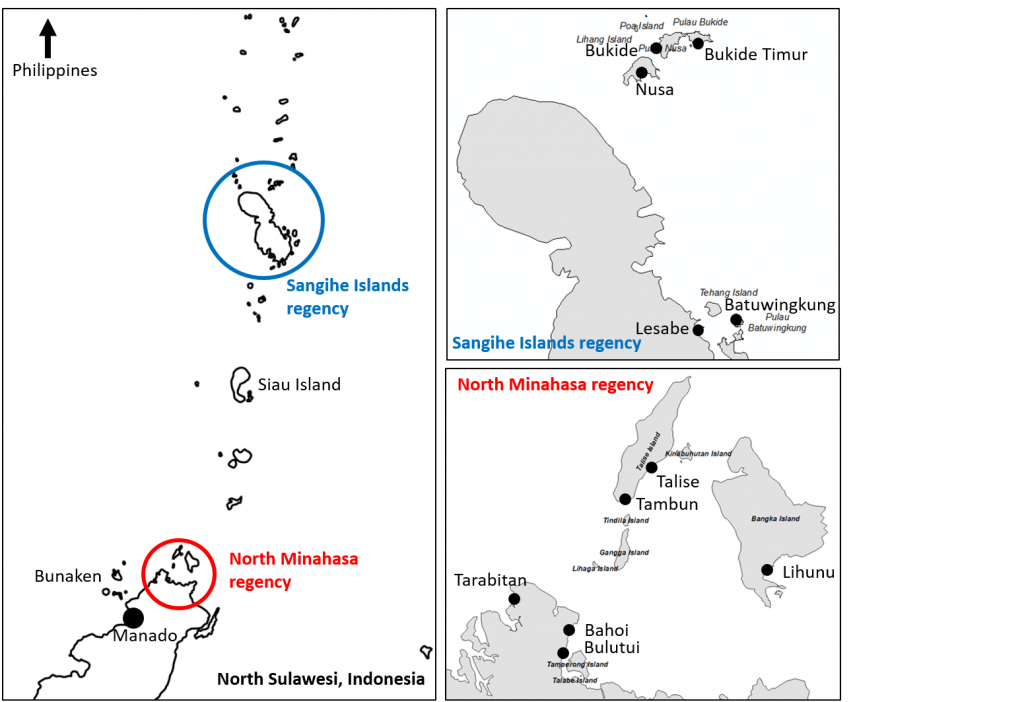

The project took place in the province of North Sulawesi in North Minahasa regency (in the villages of Bahoi, Bulutui, Tarabitan, Tambun, Talise, Lihunu) and Sangihe Islands regency (in the villlages of Lesabe, Batuwingkung, Nusa, Bukide, and Bukide Timur).

What did you do during your mission to Sulawesi? What did you find as a result of your research?

The mission is Sulawesi lasted four months, with field work data collection in 11 villages. For information about dugong, the dugong questionnaire from UNEP/CMS 2010 has been adapted and translated in Indonesian. Also, the order of the questions has been changed to facilitate the interviews with local fishermen. The questionnaire used contains eight parts:

- Contact information

- Interviewee background (age; occupation;)

- Dugong and seagrass perception: dugong definition; legends; threats; roles; protection; law;

- Dugong sightings: frequency, circumstances; habitats;

- Threats: bycatch and hunting in the last 5 years: consumption; bycatch; hunting

- Other threat information: stranded; dead; injured dugongs

- Fishing practices: boat; gear; location; frequency.

- Others: sea turtles; dolphins; sharks

The interviews were conducted with staff members from Yapeka in local language. We showed to the respondents maps to localize information on dugong sightings and fishing practices. One hundred eighty interviews were conducted; the majority with local fishermen and few of them with dive instructor from resorts.

Seagrass data was collected using direct observations with a combination of transect lines and quadrates. The coastline of each village was divided in 13 to 30 sampling sites distant of 200-250m from each other. At each sampling site, data was collected on a transect perpendicular to the coastline every 10m with a quadrat. The following parameters were recorded: seagrass cover; seagrass species; sediment type; algae cover; coral cover; and epiphytes. In North Minahasa, 120 transects and 1459 quadrats were realized and in Sangihe 63 transects and 955 quadrats.

A total of 305 dugong sightings in five years were reported by the respondents.

We found dugong feeding tracks around Lihunu village (North Minahasa) and spotted a dugong from the boat in Tarabitan village, Lihunu village and between Lesabe and Batuwingkung (Sangihe Islands). We found evidences that dugongs are still present in North Sulawesi and seen frequently by local fishermen. Dugongs are really vulnerable for seagrass abundance and seagrass composition and fishermen behaviour. We are currently working on a scientific publication which will provide insight on the relation between fishermen practices and dugongs and the identification of critical conservation areas. In the area, dugongs seem to suffer from interactions with gill netters and an intense boat traffic.

We found dugong feeding tracks around Lihunu village (North Minahasa) and spotted a dugong from the boat in Tarabitan village, Lihunu village and between Lesabe and Batuwingkung (Sangihe Islands). We found evidences that dugongs are still present in North Sulawesi and seen frequently by local fishermen. Dugongs are really vulnerable for seagrass abundance and seagrass composition and fishermen behaviour. We are currently working on a scientific publication which will provide insight on the relation between fishermen practices and dugongs and the identification of critical conservation areas. In the area, dugongs seem to suffer from interactions with gill netters and an intense boat traffic.

Eleven species of seagrasses have been observed in North Sulawesi: E. acoroides, H. ovalis, H. minor, H. decipiens, T. hempirichii, C. serrulata, C. rotundata, H. pinifolia, H. univervis, S. isoetifolium, and T. ciliatum. T. hemprichii and E. acoroides are the most dominant seagrass species. Pioneer seagrass beds abundance are particularly critical for dugong populations. In North Sulawesi, pioneer seagrass beds (e;g H. pinifolia and C. rotundata) are located mostly in the intertidal areas and accessible at high tide to dugongs.

Why is it important to research seagrass and dugongs? Where is this information used? How will the information from your research be used?

The dugong is a threatened species classified as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015. It might be especially vulnerable in Indonesia because of the high anthropogenic risks. In addition, effective enforcement of conservation regulations and accurate exhaustive monitoring are lacking.

A healthy dugong population could make the dugong become a flagship species in the area in terms of conservation and ecotourism development.

Knowledge on seagrass distribution and condition is a necessary prerequisite for management actions and consequently the survival of dugongs. In Indonesia, dugongs use a limited number of seagrass meadows containing enough nutrient-rich seagrass species called core areas and hence the repartition of these areas is an important feature for conservation management.

North Minahasa community rely to seagrass ecosystem services (e.g. for protein sources) heavily for household use. North Minahasa communities are the most intensive user of seagrass resources compared with Sangihe, Lombok and Sumba (all 4 islands in Wallacea biodiversity hotspot). Therefore, a proper seagrass sustainable management plan is critical in the area to maintain food security and biodiversity conservation.

The information from this research is mainly use by the NGO Yapeka which runs projects for managing and creating community based MPAs. Data on the characteristics of seagrass resources, such as where species of seagrasses occur and in what proportions, and whether damaged meadows can be repaired or rehabilitated are needed to develop a relevant management plan. Data on dugongs supports conservation plans and educational actions. The areas of high priority are identified and measures could be taken. This information serves as a base for MPAs and coastal management (in village and/or provincial level) and also to raise awareness about dugongs and seagrass ecosystems.

What were the greatest challenges that you faced during your field work, as a young researcher?

The first challenge was to find solutions for fund the research and especially costs related to travel expenses and visas. As a young researcher, it is difficult to find organizations who accept to support such project.

The second challenge was to design a research plan achievable in the time frame accorded and with the resource available. Indeed, my initial research protocol was too ambitious and I had to adapt it once in the field. Working in Indonesia, in small remote villages, added supplementary constraints that slow the progression (limited access to internet; and language barrier mostly).

What advice would give to those who are working on dugong and seagrass research, in general and in specifically in Indonesia?

To my colleagues who are going to work on dugong and seagrass research I advise to:

- Be realistic and define your research question precisely. Define a realistic research plan, not too ambitious but very detailed with clear aim will enable you to collect high-quality data and answer the initial research question.

- Be adaptable. In the field you will always encounter difficulties or unpredictable events. Be ready to adapt yourself according to the circumstances.

- Be passionate. Research on seagrass and dugong require to be very patient, determined, and ready to work hard.

Specific to Indonesia I advise to:

- Learn Indonesian language prior to departure. It helps a lot to achieve field work in better conditions and gain in efficiency.

- Be really rigorous with administrative documents and specific authorizations.

- Go meet the locals. They have a lot of knowledge to share and will make you research experience even more rich in term of social experience. Do not be afraid of changing your habits.

What would you like to do after this research is over? Are you planning to continue studying dugongs and their habitats?

I achieved to write in September 2016 my master thesis report entitled: “Status of dugongs in relation to intertidal and shallow subtidal seagrass beds and human indices threats in North Sulawesi, Indonesia.”

I graduated in October 2016 and I am currently working on scientific papers to make the most of this research.

I got very interested in dugongs when I undertook a literature review on the information available on dugongs and realized the lack of knowledge we have on this species very vulnerable. That motivate me to continue researching on dugongs. I am currently looking for new opportunities to work on dugongs.

Tells us briefly about yourself?

My name is Angélique Bonnet from France. Since my youngest age I have been fascinated by wildlife and the high diversity and complexity in all the living creatures. Therefore, I decided to study biology. My interests in marine conservation grew as I was volunteering for an NGO in Greece two years ago. Last year, I stopped my degree for one year to achieve work opportunities abroad; for instance, I studied the effects of climate change on fish behaviour in Australia. Lately, I did an Erasmus exchange program at Wageningen University to specialize in marine conservation and did my master thesis on dugong conservation. I graduated in October 2016 and I pursue my work on marine conservation research projects and marine biodiversity monitoring. I have broad research interests in population ecology, behaviour; impact assessment; and conservation, particularly on marine mammals and their habitats.