Our partners in Mozambique recently sent us a series of photographs of fish drying in the sun on wooden racks. “Why would our project partners send us these photos? What do dried fish have to do with dugong conservation?” we wondered. And, then, we began making some connections and observations…

Why do we dry our foods?

Drying food removes water. Without water bacteria and mold cannot grow. Once dry, food can be kept for many months – even years – providing it doesn’t get wet again.

How long have we been drying our foods?

Drying food is an ancient method of food preservation. It has been around for thousands of years – who knows? – maybe tens, or even hundreds, of thousands of years ().

How do we dry food?

Drying is typically accomplished through passive means, such as sunlight and wind and sometimes, more active means – such as adding salt or applying smoke from burning wood. Modern dehydrators are also used.

Drying fish in Mozambique seems to happen on table-like structures made from palm fronds with cross members made from another tree – possibly mangrove.

Fish are spread out horizontally to dry. In other places fish are hung vertically, as in this photograph from India.

The fish in Mozambique seem to be of various species – mostly small ones – that are all caught by a fishing net. The fish are first gutted. Then laid to dry in the sun.

Dried fish is inexpensive to produce, store and transport.

Drying fish is a necessity in the villages that dot the Indian Ocean shorelines. The only other option would be to refrigerate it or put it on ice. Refrigeration and ice making requires electricity. Electricity may be unavailable, scarce, intermittent, and/or expensive.

Good and Regular supply of power might be something that most of us take for granted, but this is not the case for many coastal areas where the energy supply is limited or not existent and communities need to prioritise basic needs for electricity. These villages may not be connected to an electricity grid. Even if they were connected the electricity may be reserved for basic community needs (hospitals, clinics) and its probably intermittent and unreliable. What limited electricity may exist likely comes from a generator – also an expensive and unreliable source of power.

Dried fish is easy to transport for commercial purposes. Transportation of fresh fish to a market requires insulated trucks fitted with iceboxes or refrigeration units – a method that increases the price of the fish at the market. In addition, not all communities can afford to purchase and maintain a refrigerated truck.

It is only in access to a constant and relatively inexpensive supply of electricity, that some of the world’s population have moved away from perishable food and moved toward refrigeration as a method of preservation.

Poor coastal areas today still need to store fish for a long time to compensate for times when fish may not be available due to weather, illness, seasons, etc. To keep dried fish is simple. To keep fresh fish for long periods requires freezing – and again we are back to electricity.

Dried Fish and Conservation.

We wouldn’t be a group of conservationists if we didn’t also discuss the impact of fishing on Dugong and Seagrass.

Of course, the practice of drying fish has no impact. But fishing does!

Fishermen do not seem to be directly targeting dugong. Instead catching a dugong in a net is usually unintentional. Such unintentional catching is also known as by-catch. The dugong get trapped in the nets fishermen are using to catch the small-size fish. The same fish destined for the drying table.

The unintentional trapping happens when someone isn’t paying attention to their nets. In the case of set nets, fishermen go ashore leaving the net unattended and return many hours later to retrieve their catch. It is during these times of absence that dugongs get trapped and suffocate.

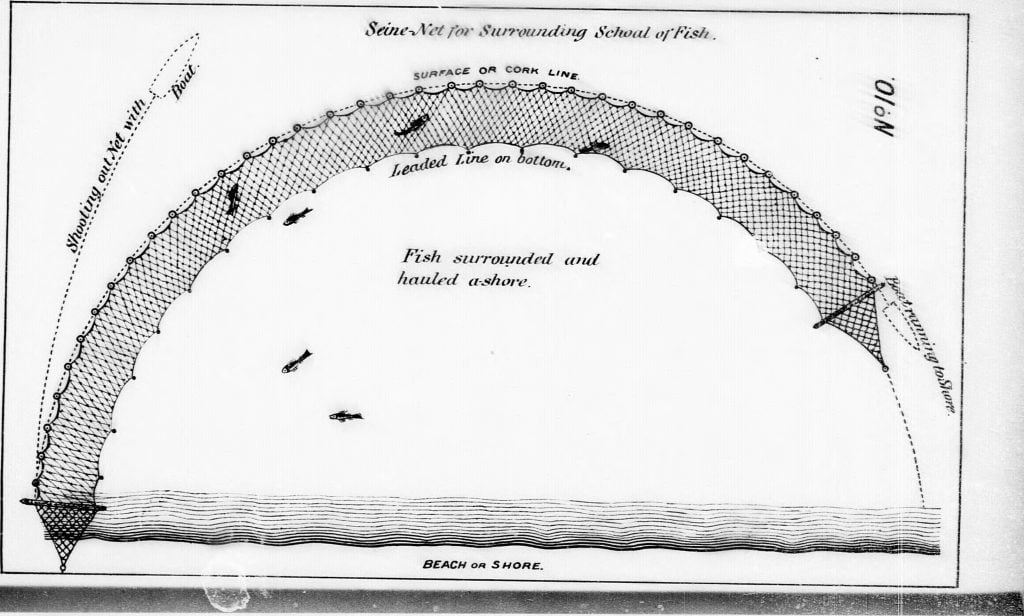

In the case of seine net, one end of a long net is ferried out from shore by boat which eventually brings the same end back to shore. This forms a half circle with the shore cutting across the diameter, as demonstrated in the image below. Dugong are sometimes caught in the half circle. Fishermen only find the netted dugong when the entire net rigging is brought to shore. There have been three reports of dugong mortalities in Mozambique so far in 2017. All of these mortalities were attributed to seine net fishing

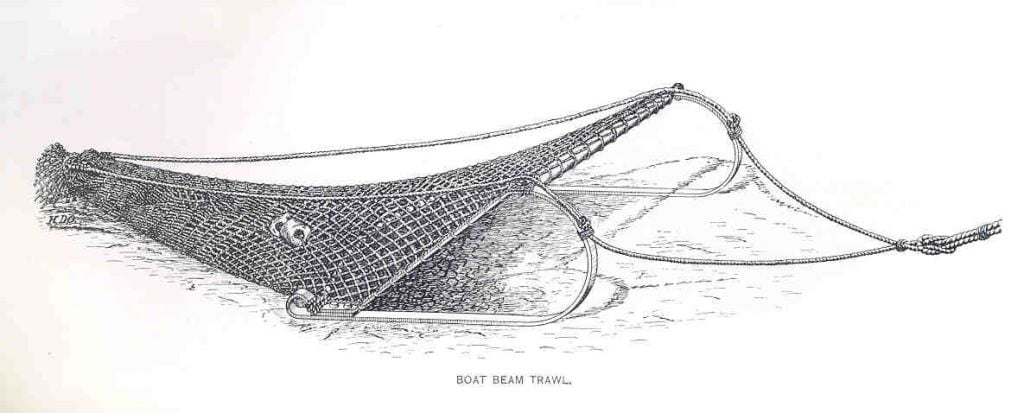

A significant threat to seagrass is trawling – dragging a heavy net behind a boat. When the net is dragged on the bottom, it uproots the seagrass and kills it.

The Dugong and Seagrass Conservation Project is helping help people sustain their livelihoods and protecting at the same time the seagrasses and their inhabitants. Our partners in Mozambique have been working with local fishers and their families to raise their awareness about how their fishing methods and gear affect seagrasses and why this matters to their livelihoods. They are building capacities and understanding among local fishermen on how current practices and seasons should respond the increasing demand for marine resources, so that the sea continues to secure food and income for their communities.

Cooking Dried Fish

We looked up a few recipes for cooking dried fish. Many of the recipes online come from Sri Lanka and India. The video that caught our eye, not only because of the traditional methods, but also because the finished product looks so inviting.

Dried fish slideshow from Mozambique

We thought you might like to see the photos that inspired our blog post. Thanks to Dugongos, our partners in Mozambique, for sending in the photos.